Interfaith Dialogue, Language and the Definition of Terms

Gamelan fusion orchestra Kiai Kanjeng and prominent Indonesian artist and activist Emha Ainun Nadjib have been touring the Netherlands on a program of concerts and seminars. They embarked on Monday 6 0ctober and are scheduled to return to Indonesia two weeks later on Monday 20 October. The group are no strangers to touring European countries, having played extensively in the UK on two tours, including Scotland, as well as Germany, Finland and Italy.

The tour was entitled Voices & Visions: An Indonesian Muslim Poet Sings a Multifaceted Society and described in promotional materials as an intercultural and inter-religious project, fostered by the Protestant Church in The Netherlands and executed by the Centre for Reflection of the Protestant Church and its Hendrik Kraemer Institute, in close cooperation with Java Enterprise (Indonesia in Events, Music, Food, Dance & Culture).

In March the Jakarta Post wrote that the invitation was intended to help deal with possible negative impacts resulting from the screening of the controversial film on Islam by Geert Wilders, “Fitna”, which was due for screening nationwide in the Netherlands on 24 March. Emha said at the time that the group were invited to “bridge the parties that may be dragged into conflicts due to the screening of the film." He said it would not be the first time he and his group had been invited to calm tensions between conflicting communities through music and cultural performances.

It was perhaps no surprise that Kiai Kenjeng were selected to make the trip. Academics and community leaders in the Netherlands have long been aware of Emha’s work in the field of interfaith relations. Behind the initiative were Prof. Nelly Van Doren of the Valparaiso University, Indiana, dan Aart Verbug of the Centre for Reflection of the Protestant Church and the Hendrik Kraemer Institute. Emha’s career in Indonesia has not been without controversy. He has long defended minority groups such as the Ahmadiyah sect, who have been persecuted by larger, more mainstream Islamic organisations seeking to force the government to issue a ban on Ahmadiyah’s teachings and activities.

Few people may know however that while Emha has worked the interests of minority groups, he has also provided guidance and advice to more hardline groups, working to moderate some of their more extreme intentions and plans. He is as comfortable in meetings with the Islamic Defenders’ Front (FPI) as he is with the Jaringan Islam Liberal (Liberal Islam Network) and has defended the positions of both, chastising each for the extremity of their positions. Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia, known for their demonstrations in Jakarta and Surabaya including those held outside the Netherlands Embassy in protest at the film “Fitna”, have visited his complex in Yogyakarta to seek his counsel. In 2006, Ismail Yusanto, Spokesman for Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) wrote that Emha:

“...speaks of politics, but without politicising; of the dilapidated buraucracy, but not as a bureaucrat: of deceitful business, but neither is he a businessman, of Islam and caring, yet he is not an Ulama.” Emha works to raise awareness, he wrote, speaking to our very conciousness itself. As examples Yusanto referred to Emha’s art and writing, whch he termed a matter of conciousness-raising, citing Emha’s poetry, the epic drama, Lautan Jilbab (The Sea Of Veils), and his short broadcasts on Jakarta’s Radio Delta FM.

Emha was also asked to assist in calming the supporters of Abu Bakr Ba’asyir prior to Ba’asyir’s imprisonment for charges relating to the 2002 Bali Bombing. Ba’asyir’s followers had threatened retaliation for the imprisonment of their leader but were pacified by Emha who was able to overcome their anger and frustration.

Taking no sides, while defending the rights of every group to a voice, Emha has become a trusted peacemaker and moderator. The nature and substance of Kiai Kanjeng’s performances support interfaith dialogue. The gamelan orchestra has earned a reputation for dynamic concerts filled with the sounds and voices of different cultures and countries. During their first concerts in the Netherlands they played in churches to large audiences composed of a multitude of people from a wide variety national groupings resident in the Netherlands, from Turkey, Pakistan, Morocco, Iraq and Iran, and of course from the Netherlands. Their repertoire included songs in Dutch, Arabic and English, from both Christian and Muslim cultures. They included versions of universal western classics such as Imagine, Stand By Me, Everything I do and Love Story; all given the Kiai Kanjeng gamelan treatment. A highpoint of each concert was a climactic rendition of a song with lyrics by the Lebanese singer, Majdah Rumi, adapted by Kiai Kanjeng and delivered in Arabic and English by Novia Kolapaking, Emha’s wife; an artist in her own right and at the peak of her powers. A moving love song, “Khalimah” moves and shifts through more than six minutes of pounding gamelan, percussion, electric guitars and strings, a perfect conclusion to a powerful concert.

In 2005 KiaiKanjeng were touring in Italy when news of the death of Pope John Paul II broke. A festival at which the group were scheduled to perform was cancelled but Kiai Kanjeng were asked to play on the occasion of the pope’s funeral. They wrote an original piece in his honour entitled “O Papa” and, when Emha recounted the story at concerts in the Netherlands, Kiai Kanjeng would play it, invoking a deep response from multicultural audiences.

In late 2005 and early 2006 Emha also commented on the growing controversy surrounding the Danish caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. He wrote of the great tolerance practised and encouraged by the Prophet Muhammad, who was persecuted and abused for many of the early years of his mission. Emha noted that Denmark, as a part of Scandinavia, sets great store by the maturity of the democracy that it has achieved. One of the ‘sacred verses’ of democracy is freedom of expression. The freedom of the press is held in particularly high regard. Emha wrote that Allah in the Holy Koran provides a clear moral response to a person insulted or abused. The person has a judicial right to retaliate to the same degree, but this “right” is sheathed in the Koranic phrase: “if you can forgive, it would be better in My eyes."

Emha wrote that a number of his companions had asked him whether he was not upset or angry at the caricatures. He replied that:

“With all insults and abuses I love the Prophet of Allah, Muhammad. He was the man most beloved of Allah. How could there be one molecule of my living being that is not filled with love for him? The extent of the capacity of my love for him brings me to a state of intoxication, experiencing giddier heights than ever reached before, hunched up in corners so tight I could not possibly be more restricted, love that is greater than life or death itself. All insults, irritations, abuses and faults, as brutal as they can possibly be, could not decrease the extent of my capacity for love even 1 cc. Love for the Prophet fills my soul and my life, and my love for family, friends, country and nation, for the entire community: becomes more beautiful, more filled with brightness and filled with peace, in the womb of my love for him. Whatever the potency of any insult, it cannot compare to the absolute certainty of death, while my love for him rises above life and death. And if the prophet was never angry, if he was kind and always forgave those who insulted him: how could a person who loves the Prophet of Allah dare to offer anything but kindness and forgiveness?”

Insults, he wrote, serve to raise Muhammad higher in his heaven. He wrote of the great insight, clarity of thought, strength and calm which he had gained from the example of the Prophet’s life – none of which could be reduced by any insult. He concluded by asking whether those angered by the caricatures had studied the history of the Danes; their ways of thought and experiences, and if so, were they still shocked by their modes of expression? Based on what expression of ‘Danish-ness’ and with what perspective on reality would you expect anything but caricatures like those?

Emha referred to those Muslims who had been angry, enraged or even riotous in reaction to the caricatures. He questioned why anyone would be surprised at their reaction or expect that they would behave in any other way. Would you expect them to demonstrate the forbearance of the Prophet? Based on what tradition of Islamic teaching or on the religious culture of what group of Muslims, or on what state of maturity, wisdom, and humanity, he asked, do you regard their rage?

It is perhaps no surprise therefore that based on this background of inter-faith and intercultural comment and engagement, the Centre for Reflection of the Protestant Church and its Hendrik Kraemer Institute made their invitation to Emha and KiaiKanjeng.

On Thursday 9 October, with a number of successful concerts behind him, Emha and Novia were invited to meet with Mr. Edwin Keijzer, Advisor for Relations with the Islamic World, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The meeting was held at the Indonesian embassy and hosted there by Mr. Siswo Pramono, Minister Counsellor for Political Affairs. A number of key issues emerged during the meeting which had to do with the terms and language used to describe interfaith dialogue, but which may impact on its very success.

The main point focused on whether dialogue should be labelled interfaith or equipped with other language which would not refer explicitly to religion. Instead such dialogue would refer to factors of class, age, culture or gender. By removing the term faith, Mr. Keijzer proposed to facilitate an engagement on grounds other than religion, thereby affording access to dialogue with communities and individuals who do not, or prefer not to, define themselves in terms of a religious affiliation. This, argued Mr. Keijzer, would be a more fitting approach for the Dutch context, where, though many people would define themselves as Christian, many would not choose to represent that affiliation in a dialogue.

Mr. Keijzer argued that the use of the term interfaith dialogue would lead people to infer that faiths were somehow at odds, and therefore required dialogue to overcome the apparent difficulties between them, thereby perpetuating an oppositional juxtaposition of faiths and hindering the inference of a sense of harmony. This, argued Mr. Keijzer, could be the manner in which the visit of Emha and Kiai Kanjeng could be viewed if it was presented as an inter-religious project. He argued that Dutch people, despite owning to a religious affiliation, would not identify themselves primarily in terms of that identity, and neither would they seek to use a religious framework in engaging with other groups.

Emha countered that his visit had been made in response to an invitation from a faith-based organisation for which the program was already formed and fixed. He said that ordinarily he would prefer not to appear overtly as a Muslim artist, and indeed works hard not to do so, favouring instead a fully humanist approach in which one’s religious identification, if any, would not determine how one was perceived. He also said that the notion that one could ignore people’s religious identity would be difficult in some cultures. In the major Islamic societies of the Middle East and Asia people attach great importance to their identities as Muslims over and above notions of nationality or other social affiliations. In engaging the peoples of the Islamic world it would be very difficult to label them in any way that did not first and foremost identify them as Muslims.

Indonesia’s state ideology of Pancasila lends itself very well to the promotion of interfaith dialogue in a vast country which recognises five major religions and which still requires its citizens by law to adopt and be identified in terms of a religion. Indonesia has also hosted a number of important interfaith dialogues including the Global Trialogue in 2000, which is a regular conference of representatives of the three monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam organised by the Temple University and Prof. Leonard Swidler. However, this conference and many other interfaith dialogues are based on the religious affiliations of delegates and the interests of the followers of the religion that delegates represent. To follow Mr. Keijzer’s line of thinking, these people would be required to identify themselves in ways other than religious affiliation.

Emha and all present were extremely pleased to have had the opportunity of this discussion. While it is clear that faith communities seeking to engage with each other across cultures would identify themselves primarily in terms of a religious identity, it is by no means certain that governments would seek to do so. Both approaches however are important and useful in human interaction. What is in a name after all? Dialogue across cultures is vital and meaningful, whatever terms are used to describe it, but those wishing to make progress in inter-faith dialogue may find faith communities resistant to that approach.

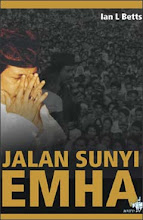

By Ian L. Betts, the author of a book on the work of Emha and Kiai Kanjeng entitled “Jalan Sunyi Emha” (The Silent Path). He accompanied Emha Ainun Nadjib and Kiai Kanjeng on this tour.

Gamelan fusion orchestra Kiai Kanjeng and prominent Indonesian artist and activist Emha Ainun Nadjib have been touring the Netherlands on a program of concerts and seminars. They embarked on Monday 6 0ctober and are scheduled to return to Indonesia two weeks later on Monday 20 October. The group are no strangers to touring European countries, having played extensively in the UK on two tours, including Scotland, as well as Germany, Finland and Italy.

The tour was entitled Voices & Visions: An Indonesian Muslim Poet Sings a Multifaceted Society and described in promotional materials as an intercultural and inter-religious project, fostered by the Protestant Church in The Netherlands and executed by the Centre for Reflection of the Protestant Church and its Hendrik Kraemer Institute, in close cooperation with Java Enterprise (Indonesia in Events, Music, Food, Dance & Culture).

In March the Jakarta Post wrote that the invitation was intended to help deal with possible negative impacts resulting from the screening of the controversial film on Islam by Geert Wilders, “Fitna”, which was due for screening nationwide in the Netherlands on 24 March. Emha said at the time that the group were invited to “bridge the parties that may be dragged into conflicts due to the screening of the film." He said it would not be the first time he and his group had been invited to calm tensions between conflicting communities through music and cultural performances.

It was perhaps no surprise that Kiai Kenjeng were selected to make the trip. Academics and community leaders in the Netherlands have long been aware of Emha’s work in the field of interfaith relations. Behind the initiative were Prof. Nelly Van Doren of the Valparaiso University, Indiana, dan Aart Verbug of the Centre for Reflection of the Protestant Church and the Hendrik Kraemer Institute. Emha’s career in Indonesia has not been without controversy. He has long defended minority groups such as the Ahmadiyah sect, who have been persecuted by larger, more mainstream Islamic organisations seeking to force the government to issue a ban on Ahmadiyah’s teachings and activities.

Few people may know however that while Emha has worked the interests of minority groups, he has also provided guidance and advice to more hardline groups, working to moderate some of their more extreme intentions and plans. He is as comfortable in meetings with the Islamic Defenders’ Front (FPI) as he is with the Jaringan Islam Liberal (Liberal Islam Network) and has defended the positions of both, chastising each for the extremity of their positions. Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia, known for their demonstrations in Jakarta and Surabaya including those held outside the Netherlands Embassy in protest at the film “Fitna”, have visited his complex in Yogyakarta to seek his counsel. In 2006, Ismail Yusanto, Spokesman for Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) wrote that Emha:

“...speaks of politics, but without politicising; of the dilapidated buraucracy, but not as a bureaucrat: of deceitful business, but neither is he a businessman, of Islam and caring, yet he is not an Ulama.” Emha works to raise awareness, he wrote, speaking to our very conciousness itself. As examples Yusanto referred to Emha’s art and writing, whch he termed a matter of conciousness-raising, citing Emha’s poetry, the epic drama, Lautan Jilbab (The Sea Of Veils), and his short broadcasts on Jakarta’s Radio Delta FM.

Emha was also asked to assist in calming the supporters of Abu Bakr Ba’asyir prior to Ba’asyir’s imprisonment for charges relating to the 2002 Bali Bombing. Ba’asyir’s followers had threatened retaliation for the imprisonment of their leader but were pacified by Emha who was able to overcome their anger and frustration.

Taking no sides, while defending the rights of every group to a voice, Emha has become a trusted peacemaker and moderator. The nature and substance of Kiai Kanjeng’s performances support interfaith dialogue. The gamelan orchestra has earned a reputation for dynamic concerts filled with the sounds and voices of different cultures and countries. During their first concerts in the Netherlands they played in churches to large audiences composed of a multitude of people from a wide variety national groupings resident in the Netherlands, from Turkey, Pakistan, Morocco, Iraq and Iran, and of course from the Netherlands. Their repertoire included songs in Dutch, Arabic and English, from both Christian and Muslim cultures. They included versions of universal western classics such as Imagine, Stand By Me, Everything I do and Love Story; all given the Kiai Kanjeng gamelan treatment. A highpoint of each concert was a climactic rendition of a song with lyrics by the Lebanese singer, Majdah Rumi, adapted by Kiai Kanjeng and delivered in Arabic and English by Novia Kolapaking, Emha’s wife; an artist in her own right and at the peak of her powers. A moving love song, “Khalimah” moves and shifts through more than six minutes of pounding gamelan, percussion, electric guitars and strings, a perfect conclusion to a powerful concert.

In 2005 KiaiKanjeng were touring in Italy when news of the death of Pope John Paul II broke. A festival at which the group were scheduled to perform was cancelled but Kiai Kanjeng were asked to play on the occasion of the pope’s funeral. They wrote an original piece in his honour entitled “O Papa” and, when Emha recounted the story at concerts in the Netherlands, Kiai Kanjeng would play it, invoking a deep response from multicultural audiences.

In late 2005 and early 2006 Emha also commented on the growing controversy surrounding the Danish caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. He wrote of the great tolerance practised and encouraged by the Prophet Muhammad, who was persecuted and abused for many of the early years of his mission. Emha noted that Denmark, as a part of Scandinavia, sets great store by the maturity of the democracy that it has achieved. One of the ‘sacred verses’ of democracy is freedom of expression. The freedom of the press is held in particularly high regard. Emha wrote that Allah in the Holy Koran provides a clear moral response to a person insulted or abused. The person has a judicial right to retaliate to the same degree, but this “right” is sheathed in the Koranic phrase: “if you can forgive, it would be better in My eyes."

Emha wrote that a number of his companions had asked him whether he was not upset or angry at the caricatures. He replied that:

“With all insults and abuses I love the Prophet of Allah, Muhammad. He was the man most beloved of Allah. How could there be one molecule of my living being that is not filled with love for him? The extent of the capacity of my love for him brings me to a state of intoxication, experiencing giddier heights than ever reached before, hunched up in corners so tight I could not possibly be more restricted, love that is greater than life or death itself. All insults, irritations, abuses and faults, as brutal as they can possibly be, could not decrease the extent of my capacity for love even 1 cc. Love for the Prophet fills my soul and my life, and my love for family, friends, country and nation, for the entire community: becomes more beautiful, more filled with brightness and filled with peace, in the womb of my love for him. Whatever the potency of any insult, it cannot compare to the absolute certainty of death, while my love for him rises above life and death. And if the prophet was never angry, if he was kind and always forgave those who insulted him: how could a person who loves the Prophet of Allah dare to offer anything but kindness and forgiveness?”

Insults, he wrote, serve to raise Muhammad higher in his heaven. He wrote of the great insight, clarity of thought, strength and calm which he had gained from the example of the Prophet’s life – none of which could be reduced by any insult. He concluded by asking whether those angered by the caricatures had studied the history of the Danes; their ways of thought and experiences, and if so, were they still shocked by their modes of expression? Based on what expression of ‘Danish-ness’ and with what perspective on reality would you expect anything but caricatures like those?

Emha referred to those Muslims who had been angry, enraged or even riotous in reaction to the caricatures. He questioned why anyone would be surprised at their reaction or expect that they would behave in any other way. Would you expect them to demonstrate the forbearance of the Prophet? Based on what tradition of Islamic teaching or on the religious culture of what group of Muslims, or on what state of maturity, wisdom, and humanity, he asked, do you regard their rage?

It is perhaps no surprise therefore that based on this background of inter-faith and intercultural comment and engagement, the Centre for Reflection of the Protestant Church and its Hendrik Kraemer Institute made their invitation to Emha and KiaiKanjeng.

On Thursday 9 October, with a number of successful concerts behind him, Emha and Novia were invited to meet with Mr. Edwin Keijzer, Advisor for Relations with the Islamic World, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The meeting was held at the Indonesian embassy and hosted there by Mr. Siswo Pramono, Minister Counsellor for Political Affairs. A number of key issues emerged during the meeting which had to do with the terms and language used to describe interfaith dialogue, but which may impact on its very success.

The main point focused on whether dialogue should be labelled interfaith or equipped with other language which would not refer explicitly to religion. Instead such dialogue would refer to factors of class, age, culture or gender. By removing the term faith, Mr. Keijzer proposed to facilitate an engagement on grounds other than religion, thereby affording access to dialogue with communities and individuals who do not, or prefer not to, define themselves in terms of a religious affiliation. This, argued Mr. Keijzer, would be a more fitting approach for the Dutch context, where, though many people would define themselves as Christian, many would not choose to represent that affiliation in a dialogue.

Mr. Keijzer argued that the use of the term interfaith dialogue would lead people to infer that faiths were somehow at odds, and therefore required dialogue to overcome the apparent difficulties between them, thereby perpetuating an oppositional juxtaposition of faiths and hindering the inference of a sense of harmony. This, argued Mr. Keijzer, could be the manner in which the visit of Emha and Kiai Kanjeng could be viewed if it was presented as an inter-religious project. He argued that Dutch people, despite owning to a religious affiliation, would not identify themselves primarily in terms of that identity, and neither would they seek to use a religious framework in engaging with other groups.

Emha countered that his visit had been made in response to an invitation from a faith-based organisation for which the program was already formed and fixed. He said that ordinarily he would prefer not to appear overtly as a Muslim artist, and indeed works hard not to do so, favouring instead a fully humanist approach in which one’s religious identification, if any, would not determine how one was perceived. He also said that the notion that one could ignore people’s religious identity would be difficult in some cultures. In the major Islamic societies of the Middle East and Asia people attach great importance to their identities as Muslims over and above notions of nationality or other social affiliations. In engaging the peoples of the Islamic world it would be very difficult to label them in any way that did not first and foremost identify them as Muslims.

Indonesia’s state ideology of Pancasila lends itself very well to the promotion of interfaith dialogue in a vast country which recognises five major religions and which still requires its citizens by law to adopt and be identified in terms of a religion. Indonesia has also hosted a number of important interfaith dialogues including the Global Trialogue in 2000, which is a regular conference of representatives of the three monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam organised by the Temple University and Prof. Leonard Swidler. However, this conference and many other interfaith dialogues are based on the religious affiliations of delegates and the interests of the followers of the religion that delegates represent. To follow Mr. Keijzer’s line of thinking, these people would be required to identify themselves in ways other than religious affiliation.

Emha and all present were extremely pleased to have had the opportunity of this discussion. While it is clear that faith communities seeking to engage with each other across cultures would identify themselves primarily in terms of a religious identity, it is by no means certain that governments would seek to do so. Both approaches however are important and useful in human interaction. What is in a name after all? Dialogue across cultures is vital and meaningful, whatever terms are used to describe it, but those wishing to make progress in inter-faith dialogue may find faith communities resistant to that approach.

By Ian L. Betts, the author of a book on the work of Emha and Kiai Kanjeng entitled “Jalan Sunyi Emha” (The Silent Path). He accompanied Emha Ainun Nadjib and Kiai Kanjeng on this tour.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment